Coal

Why Coal?

Mohnish Pabrai has been buying coal companies since last year. A search of 13-F filings will show that he’s pretty lonely in owning coal companies. To be fair, a lot of Mohnish’s holdings are international and not reported on 13-F filings, but ALL of his US holdings are currently coal companies.

He’s invested around $250 million in coal companies. According to his bio on his Wagons Fund page, he manages $840 million, putting his coal investment at around 25% of his fund.

His recent talks and interviews show him leaning heavily into what he calls “anomalies”. Things that are so mispriced that they shouldn’t exist. He’s referred to these in the past as “no-brainers” and of course, there’s his Dhando investor mantra of “heads I win, tails I don’t lose much.”

I’m a big fan of Mohnish, so when he concentrates in an area like this, I’m at least going to try to figure out what he’s thinking.

The Politics (or lack thereof)

Before we go further, I realize that an investment in coal wades into climate change, carbon emissions, regulation, and politics. So let’s address that with a few points.

Stocks are traded on a secondary market - meaning that unless you’re buying an IPO, or an additional offering, you’re not giving money to the company whose shares you buy. You’re buying them off of an individual or institution. It’s like buying a used car - Chevy made it, but they don’t see a dollar from the secondary transactions.

Yes, burning coal creates pollution. Regardless of your view on climate change, I think it would be hard to find someone who supports pollution. However, at this point for modern society to continue to function, coal will continue to be burned. If we could wave a magic wand and get rid of pollution, I’d be all for it. At this point, no such wand exists.

The politics and emotion around coal are exactly what has created this opportunity.

What’s the thesis?

With the politics out of the way, let’s talk about the thesis behind an investment in coal producers.

The Industry

Coal production can be broken down into 2 types:

Thermal coal - which is mainly used for power generation

Metallurgical or coking coal - which is used in steel production

The coal industry has been shrinking in recent years due to regulation, the political and social pressures we already talked about, and (most significantly) growing use of alternative sources for energy production like renewables and natural gas.

However, the global coal industry is still around $2 trillion dollars and employed around 11 million people in 2023.

Thermal VS Met Coal

Looking at Mohnish’s picks in coal companies, it quickly becomes obvious that he’s focusing on companies that produce metallurgical coal. This makes sense. One of the companies in Mohnish’s portfolio (Arch Resources) lays out the investment case for met coal nicely, so I’m going to steal some of their slides to explain it.

The Need For Steel Will Continue Growing

Steel is a huge market; as this slide says there is 10 times more steel produced than all other metals combined. Not only will we need steel to continue to make buildings, bridges, and cars, but if we’re going to transition away from polluting fuels like coal, we’ll need steel to build wind turbines, solar farms, etc.

Steel production is expected to grow at 2.3% per year through 2030, excluding China. As the next slide shows, as steel demand and production goes up, so will the need for coking coal. I want to point out a few important figures on this slide:

>70% of the world’s steel production still relies on coking coal

Steel production in Southeast Asia is expected to grow by 45% by 2030

>80% of new steelmaking capacity in Southeast Asia and India will require coking coal

This suggests that while the overall demand for coal will likely continue to fall, the demand for metallurgical, or coking coal will likely remain strong.

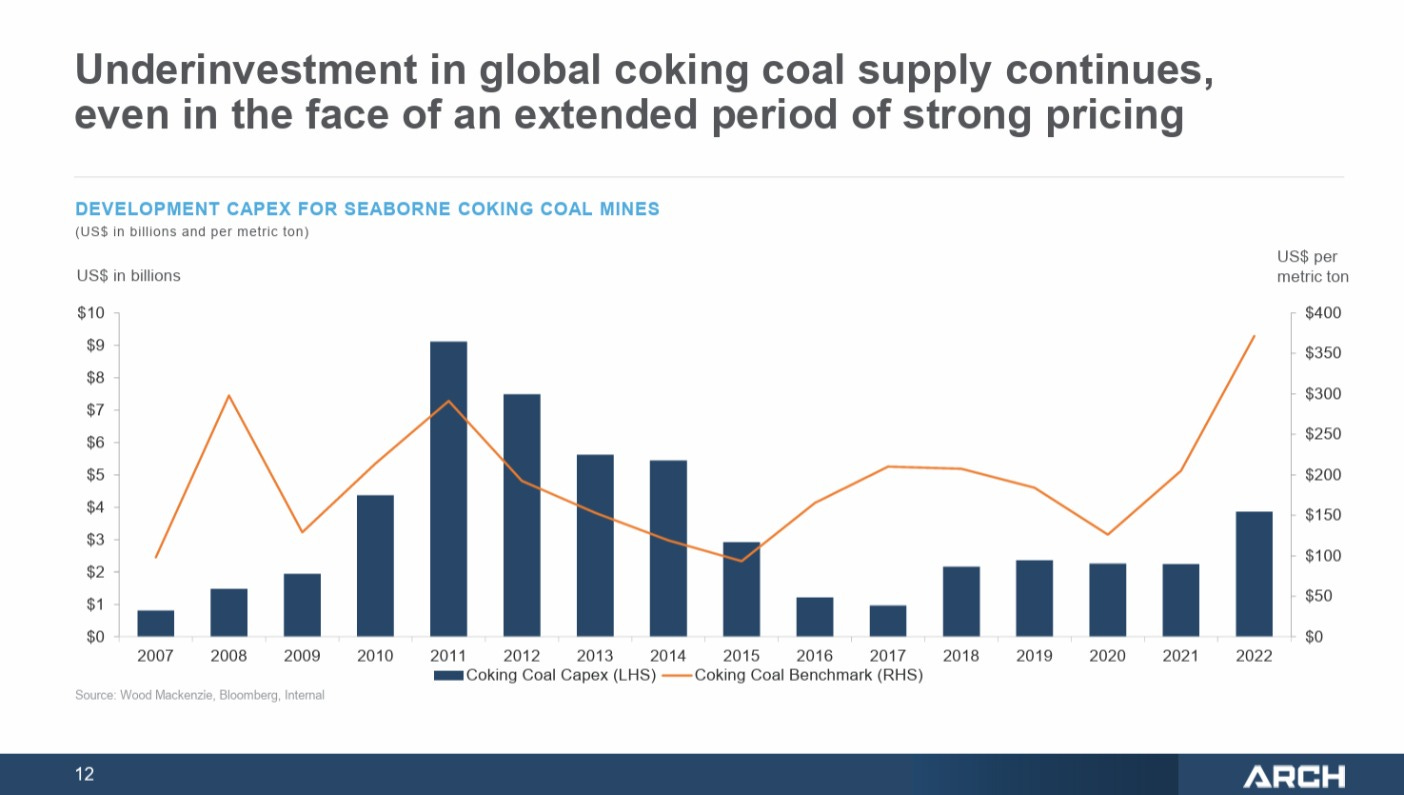

When you combine this trend with the underinvestment in new production of coking coal, the picture for companies who produce it looks much better than companies who focus on thermal coal. Prices may be volatile, but overall they will likely remain high and continue to trend up.

Politics Create The Opportunity

Despite the expected increase in steel production and coking coal demand, many large investors are not allowed to own coal companies due to ESG mandates. In fact, many of them are being forced to sell their stakes, causing low valuations.

This dynamic has caused some coal companies to shift their capital allocation away from dividends and into buybacks.

The Magic of Buybacks

The following slide comes from a presentation Mohnish did on buybacks. It shows the return on an investment with no change in earnings or multiple based on how many shares a company is able to buy back.

These companies are all below the 50% mark, so as this slide shows, we’re still in the early innings of the opportunity.

The Companies

Mohnish owns shares in 4 coal companies (in the US). They are:

Alpha Metallurgical Resources (AMR)

Arch Resources (ARCH)

Consol Energy (CEIX)

Warrior Met Coal (HCC)

I’ll do a quick overview of each. You can dive further into individual ones on your own if you wish.

Alpha Metallurgical Resources (AMR)

AMR mines met coal in Virginia and West Virginia.

In 2023 they had $3.5 billion in revenue on 16.7 million tons of coal

They produce 1/5 of all the Met coal in the US

They own 60% of the DTA export terminal in Newport News, VA

Since starting buybacks, they’ve reduced share count by about 1/3.

They stopped their dividend at the end of 2023 to focus on buybacks

They’re currently guiding for 15.5 to 16.5 million tons of coal shipped this year

Valuation

AMR has a market cap of around $5 billion. They’re at a PE of 7.6. They’ve got a strong balance sheet with a net cash position.

Here’s their FCF the past 3 years:

2021: $91.6 million

2022: $1,319 million

2023: $606 million

Assuming they can keep their FCF in the 2022/2023 range, they can buy back the whole company in 5 to 10 years.

Arch Resources (ARCH)

80% of the coal Arch produces is metallurgical coal. It comes from mines in West Virginia. The remaining 20% is thermal coal mined in Colorado and Wyoming.

Arch had $3.1 billion in revenue in 2023.

They’re guiding for 9 million tons of met coal in 2024 and a sustainable 10 million in the future, so they’re projecting sales growth.

Arch is in a net cash position on their balance sheet.

Arch primarily mines it’s met coal from longwall mines, which they say gives them a $50 per ton cost advantage over the marginal cost of production for US coking coal producers.

They also produce a high grade of coking coal - High-Vol A

They supply 30% of the world’s High-Vol A coal.

They own the remaining share of the DTA terminal in Newport News, VA.

They’ve repurchased 26% of their shares

Valuation

Arch has a market cap of around $3 billion. They’re at a PE of 6.6

Here’s their FCF:

2021: $-8.3 million

2022: $1,035 million

2023: $458 million

Again, assuming they maintain FCF at the 2022/2023 levels, they can buy back all their shares in 3 to 6 years. Add in the fact that they’re a low-cost producer of high-quality coal, and they look pretty good to me.

Consol Energy (CEIX)

Consol produces a lot of thermal coal, but they’re increasing their production of met coal. They’ve also shifted from selling domestically to exporting the majority of their coal. 70% of their current sales are exported.

In 2023, Consol mined 26 million tons of coal

3 million tons of that was met coal

They had $2.5 billion in revenue in 2023

Consol also owns an export terminal

Consol has a net cash balance sheet

They have also cut their dividend to focus on share repurchases

They’ve repurchased about 16% of their shares

Valuation

Consol has a $2.6 billion market cap currently. They’re at a PE of 4.5

Here’s their FCF:

2021: $172 million

2022: $479 million

2023: $690 million

Assuming stable FCF, they can buy back the whole company in around 5 years.

Warrior Met Coal (HCC)

Warrior produces metallurgical coal from mines in Alabama. Almost all of their coal is exported.

They produced 6.8 million tons of coal in 2023 and generated $1.6 billion in revenue.

Warrior has a net cash position on their balance sheet.

They currently operate 2 mines, both using the longwall mining technique, leading to lower production costs.

One mine produces high quality Low-Vol coal

The other produces High-Vol A coal

Both types sell at a premium to other steelmaking coals

Warrior is developing a third mine, which should start to produce coal in Q3 of this year, and be fully ramped up by Q2 of 2026.

This mine should have an even lower cost of production than the other two.

This is one of the few untapped High-Vol A reserves in the US. Warrior estimates the net present value of the mine to be $1 billion.

Warrior is still paying both a regular dividend and is returning excess cash to shareholders through special dividends. They haven’t repurchased shares since 2019.

Valuation

Warrior has a $3 billion market cap. They currently trade at a PE of 6.2.

Here’s their FCF:

2021: $293 million

2022: $633 million

2023: $209 million

Based on last year’s total dividend payments of $1.16 and the current share price, we get a dividend yield of 2%. Just the quarterly dividend yields around 0.5%, so much of the dividend returns are through the special dividends.

My guess is that Mohnish is getting into Warrior before they transition to a buyback policy as well. Either that, or he’s figuring on the dividends to climb even higher when production on the third mine really gets rolling.

The Risks

Declining Demand / Prices

When I started looking into this opportunity, my main concern was how quickly the demand for coal would decline. I was also worried that after COVID, we saw temporarily high prices, making these cyclical companies look cheap at the top of the cycle.

I’ve spent a lot of time to try to see into the future of the coal industry and what I’ve learned has really helped put these concerns to rest. Here’s why:

Met coal is REQUIRED to produce steel in a blast furnace, which is how 70% of steel is produced at this point.

The other option for making steel uses scrap in an electric arc furnace (EAF). This method still requires some pig iron to be added. That pig iron has to be produced in a blast furnace, again with met coal.

This means that there is currently no alternative to met coal if you want to make steel.

The future of metallurgical coal is clearly tied to the future of the steel industry. We’ve already said that steel production is expected to increase for the foreseeable future. Demand for met coal is also projected to rise, so demand is taken care of.

Given that the coal industry is totally mature, there is not significant supply just waiting to fill the demand. While prices may fluctuate like any commodity, we are probably not seeing artificially high pricing. In fact, over time, the price for high quality coking coal will likely increase.

The fact that Warrior is developing another mine is just more confirmation that the demand for metallurgical coal isn’t going away any time soon.

Can Coking Coal Be Replaced?

So, we’ve at least got a few years of continued demand, but can we eventually make steel without coking coal? The answer is yes, but it’s not going to happen any time soon.

To understand why, we need to go a little deeper on steel production. Coking coal serves 3 purposes in the steel making process.

Coal is needed as a reducing agent. This is the process that turns iron ore into pig iron. The chemical reaction uses carbon monoxide from the coal to get rid of the oxygen in iron ore, producing pig iron. The byproduct of this reaction is carbon dioxide.

Coal is a source of energy. It’s burned to produce heat to melt the iron and additives like nickel, chromium and manganese that influence the characteristics of the finished steel.

Coal is a necessary source of carbon in the steel making process.

Replacing Coal

Now we know why coal is needed to make steel. Can we do it without coal? Yes. Here’s how:

The alternative to using carbon monoxide from coal is to use pure hydrogen to convert iron ore into pig iron. The byproduct is water. Iron made this way is called direct-reduced iron or DRI. Sounds great! What’s the problem?

Producing industrial quantities of hydrogen is either just as bad for emissions as whatever it’s replacing, or incredibly expensive.

“Gray hydrogen” is made from fossil fuels (like natural gas) through a process called steam reforming. This still requires fossil fuels and produces a lot of emissions.

“Green hydrogen” comes from the electrolysis of water, which requires a lot of energy and is much more expensive than gray hydrogen.

The problems with industrial hydrogen production are exactly why hydrogen fuel cell cars aren’t practical replacements for internal combustion engines.

Steel is currently produced with electricity for the energy source in electric arc furnaces (EAFs). For this to reduce pollution, the electricity has to come from renewables or other “clean” sources. We currently don’t have the capacity to do this at this point.

While the majority of US steel is made in the EAF process, most global steel is not. Many global steel producers either don’t have enough scrap steel to make EAF use practical, or the infrastructure doesn’t exist to get the scrap to an EAF plant.

Assuming we converted all steelmaking to the EAF process, we’d still need a source of carbon. There are several ideas on how to do this ranging from “biochar” - essentially charcoal to using the carbon contained in the millions of discarded tires we’ve already got lying around. This is probably the easiest hurdle to overcome.

How Soon Could Coal Be Replaced?

Not very quickly. The IEA has created a net-zero by 2050 scenario that includes emissions from steelmaking. According to them, we’re not on track to meet the goals they’ve set out.

the current pipeline of low- and near zero- emission projects falls short of what is required to meet the NZE Scenario, and high- emission projects make up around two-thirds of all announced projects worldwide.

Even in their net-zero scenario, coal use doesn’t drop dramatically, and met coal use may not drop at all. Here’s what the IEA predicts for energy use in steel production:

The big blue bars represent energy from coal in global steel production. This shows a 19% reduction in energy from coal. It also shows a decline in the total energy used in steel production.

I’m not clear on exactly how we’ll use less energy when we’re projected to make more steel between now and 2030. Improved efficiencies in the process I suppose.

Don’t forget that coal isn’t just for energy. Some of the reduction in energy from coal is likely a reduction in the use of thermal coal to produce electricity used in making steel. So even if this graph is correct, it doesn’t necessarily predict a 19% reduction in the use of coking coal.

Here’s how the IEA projects the methods used to make steel changing:

The blue bars are again the ones to pay attention to. They represent global steel production using blast furnaces. The green ones at the top are production using EAF technology. This shows a 10% reduction of total production in blast furnaces by 2030. But even that number is misleading.

Remember, global steel production is expected to rise by 2% a year from now until 2030. This chart shows a gap of 8 years, which means 16% more steel will be produced in 2030. If 10% less of the total is made in blast furnaces, but we make 16% more steel, then between now and 2030 MORE steel will actually be made in blast furnaces, not less.

Regulation

When it comes to coal, you’ll no doubt hear concerns about regulation. While there have been regulations that have impacted coal in the past and no doubt will be in the future, based on what we already know about steel production, expected demand, and the requirement for metallurgical coal, I doubt regulation will kill any of these companies.

Looking into the history of regulation related to coal, most of it has been related to burning coal for electricity production. The clean air act of 1970 was the primary one that affected coal burning power plants, but since we’re not looking at thermal coal producers, these don’t impact our investment.

How about regulation on steel production? Well, 70% of the steel produced in the US is already made in EAF facilities, meaning that most US steel wouldn’t even be affected by regulation on coal use in steel making. The majority of the coal that the 4 companies we’re talking about is exported, so again, US regulation isn’t a big worry.

Also, don’t forget that the IEA says that 2/3 of new steel production is going to be by blast furnace. Even international regulation would likely grandfather in facilities already approved, so the amount of global steel made in blast furnaces might not grow quickly, but it’s unlikely to shrink.

Conclusion

Metallurgical coal producers may very well fall into Mohnish’s “anomaly” category for investments. All of these companies have solid balance sheets, with net cash positions, so they’re well positioned for a potential downturn.

They produce a necessary commodity for modern life co continue. We currently have no alternative to steel, and the majority of steel production has no alternative to metallurgical coal.

Even the IEA’s plan for net zero emissions by 2050 recognizes that the majority of global steel production will continue to happen in furnaces that require coal. Global steel production is predicted to continue to rise, and met coal production is projected to remain flat or decrease.

That will strain supply, meaning met coal producers should enjoy years of continued profitable operations, with high free cash flow generation.

These companies are trading at PE multiples below 10 due to social and political pressures, not fundamental business reasons. Management has recognized that they’re cheap and have implemented policies to return plenty of this cashflow to shareholders.

This creates what looks very much like a “heads I win, tails I don’t lose much” situation. With the very healthy balance sheets and robust cash generation, these businesses are very unlikely to go to zero. They could get cheaper temporarily, but when we’re investing in companies heavily buying back shares, that’s good!

While it’s possible that the market will decide it is ready to hold it’s nose and invest in coal companies, I don’t think that’s likely.

I think the most likely scenario is that these companies stay cheap and become multi-baggers through heavy share buybacks. I think Mohnish sees the same thing.

References:

What Is Killing the US Coal Industry? | Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR)

US joins in other nations in swearing off coal power to clean the climate | AP News

Steel Production - American Iron and Steel Institute

Coking Coal for steel production and alternatives - Front Line Action on Coal

Investors – Warrior Met Coal – Warrior Met Coal

Alpha Metallurgical Resources - Investors (alphametresources.com)

Nice piece.

"Despite the expected increase in steel production and coking coal demand, many large investors are not allowed to own coal companies due to ESG mandates. In fact, many of them are being forced to sell their stakes, causing low valuations."

Thanks for sharing this. Do you have links/sources about this? Some questions I'm trying to get more color on:

Do you know when this started taking place? Is there a risk that these mandates are withdrawn in the new future (if new president elected, etc)? Are there not loop-holes for big investors via hedge funds, or other ways to invest? What entities are/are not affected by the mandates?

Thanks

Phenomenal work, once again.