Are We Projecting The Wrong Lessons Forward?

I try very hard to always remain a bottom-up stock picker.

I know I’m not good at timing the market, or predicting the economy.

But when you’re looking for bargains, if the economy is hot, and the market is euphoric, things are tough. So you start to think about the economy and the market.

I’ve written before about how much prices matter, and how great businesses aren’t always great investments:

In that article, I showed that Buffett has rarely bought a business for much more than 15x earnings.

So I ran a pretty wide open screener to see if there’s anything that might look interesting. Here’s the criteria:

Mid-cap or larger: $2B market cap or higher

5-year EPS growth: 6% or more

Debt / equity: 50% or less

ROE: 8%

P/E: 15 or less.

Here’ s the output:

15 companies. Other than PE, I don’t think that criteria is very restrictive.

15x earnings is about the long-term average for the market.

Is This Time Different?

From 1871 to 2016, the stock market produced a compounded return of 9.07% a year. $1 turned into $319,492.

From the close 2018 to close of 2023 it was 13.9%

That’s a massive difference.

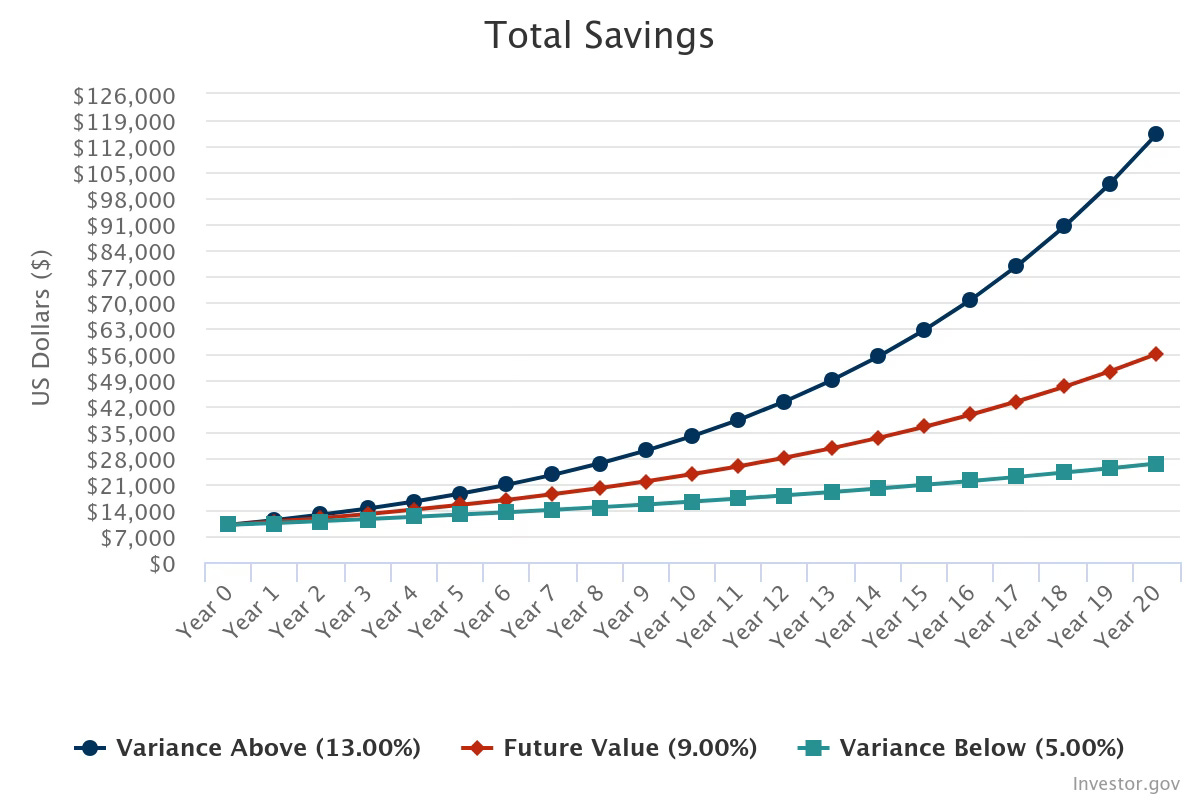

Here’s 5%, 9% and 13% compounded from $10,000 over 20 years:

9% gets you to about $60,000.

13% gets you close to $120,000.

I’m not going to predict what the next 20 years of market returns will be. I have no idea.

But I do wonder if investors are projecting forward higher than average returns, leading to willingness to pay up for stocks?

Part of me feels like the entire post 2020 time period has been abnormal, and that perhaps investors are also projecting other things forward, so I did a bit of research.

What was different about the COVID recession?

I started with the COVID-induced recession in 2020. It’s quite different from most other recessions.

1. Speed and Severity of the Contraction

COVID Recession: The global economy plunged into a recession almost overnight. In Q2 of 2020, many economies experienced their sharpest contractions in history. For example, the U.S. economy shrank by 31.4% (annualized) in Q2 2020, which was far more severe than during any previous recession, including the Great Depression and the 2008 financial crisis.

Other Recessions: Historically, recessions have unfolded more gradually due to longer-term economic imbalances (e.g., the housing bubble in 2008 or oil shocks in the 1970s).

2. Cause of the Recession

COVID Recession: It was triggered by a public health crisis rather than an economic imbalance or financial crisis. Lockdowns and social distancing measures forced entire sectors (travel, entertainment, restaurants) to shut down, leading to an economic standstill.

Other Recessions: Most past recessions were caused by economic factors like financial crises (2008), commodity price shocks (1970s), or tightening monetary policy to fight inflation (early 1980s).

3. Government Response

COVID Recession: The policy response was swift and massive. Governments and central banks launched aggressive fiscal and monetary measures, such as:

Direct cash payments.

Expanded unemployment benefits.

Large-scale central bank interventions (Federal Reserve buying bonds, cutting rates to zero, etc.).

Loan guarantees and support for businesses (Paycheck Protection Program)

Other Recessions: The response has historically been slower and smaller in scope. For example, the 2008 financial crisis saw a lot of stimulus, but it took months to fully materialize, and the fiscal response was smaller relative to the size of the economic shock.

4. Unprecedented Recovery

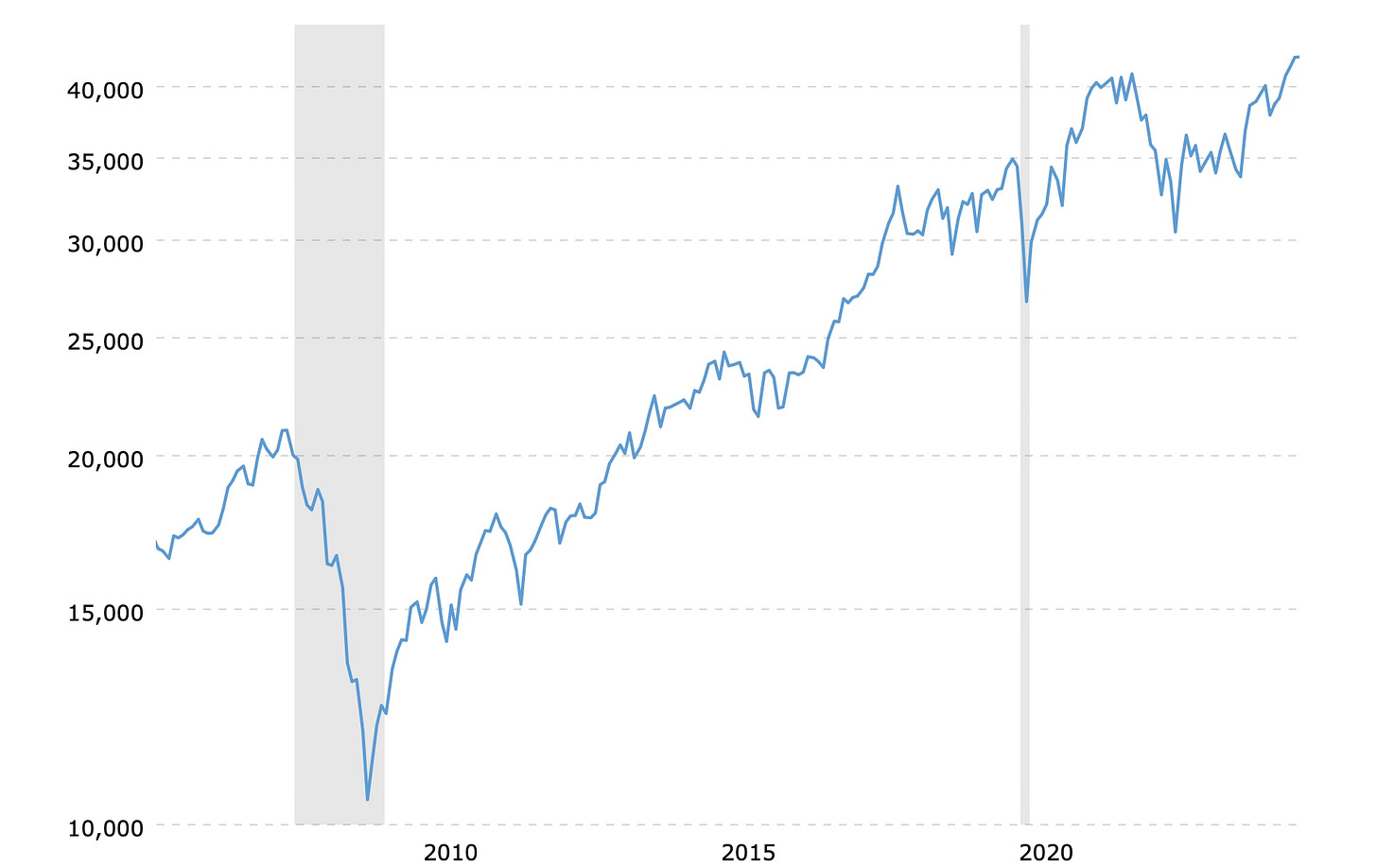

COVID Recovery: The recovery was V-shaped in many sectors. Despite the steep decline, global stock markets rebounded sharply, reaching new highs within months. In the stock market, duration matters as much as severity. Because this was over in the stock market so quickly, I’d argue it wasn’t very painful for investors. During lockdown, people bought lots of stuff. As restrictions were lifted, services rebounded too, driven by pent-up demand and strong fiscal stimulus.

Other Recessions: Recoveries are usually slower, particularly after financial crises like in 2008, which required years to recover from.

Here’s the DJIA with both the 2008 and 2020 recessions. Notice how much longer 2008 is and how much longer it took the market to recover:

COVID made the labor market weird too.

1. Speed and Magnitude of Job Losses

COVID Recession: The labor market experienced the most rapid and severe job losses on record. In the U.S., over 22 million jobs were lost in just two months (March and April 2020), driving the unemployment rate from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.7% in April 2020, the highest since the Great Depression. Other countries saw similarly drastic spikes in unemployment.

Past Recessions: Job losses have typically unfolded more gradually, often over several quarters or years. Even during the 2008 financial crisis, unemployment rose steadily but never reached the levels seen during COVID-19 in such a short time frame.

2. Sectoral Differences in Job Recovery

COVID Recession: Certain sectors, especially those dependent on face-to-face interaction (e.g., hospitality, travel, retail), experienced deep and prolonged job losses. For example, in the U.S., employment in the leisure and hospitality sector fell by nearly 50% in April 2020 and took much longer to recover compared to other sectors like tech, finance, or healthcare. Some of those workers didn’t go back, leading to continued shortages in labor today.

Other Recessions: In previous downturns, job losses were more widespread across industries, with sectors like construction, manufacturing, and finance often seeing the most significant declines. Recovery in these sectors typically took longer, but there wasn’t the stark divergence between sectors that was seen during the COVID recovery.

3. Unemployment Rate Rebound

COVID Recovery: The unemployment rate rebounded much faster than in previous recessions. In the U.S., it fell from 14.7% in April 2020 to 4.6% by October 2021, remarkable given the scale of job losses. This was largely driven by rapid rehiring in sectors that reopened after lockdowns, combined with aggressive government stimulus measures, which helped prop up consumer demand.

Past Recessions: After the 2008 financial crisis, for example, the unemployment rate remained elevated for several years, not returning to pre-crisis levels until 2016. Past recoveries were slower, as economic imbalances, financial sector issues, or structural changes in the economy took longer to resolve.

4. Wage Growth and Labor Market Tightness

COVID Recovery: Despite high unemployment in the early stages of recovery, many businesses experienced labor shortages, particularly in sectors like retail, restaurants, and healthcare. This was partly due to factors such as:

Workers reassessing their jobs and careers during the pandemic ("The Great Resignation").

Health concerns, child care challenges, and expanded unemployment benefits keeping workers temporarily out of the labor force. These shortages led to rapid wage growth in many low-wage sectors as businesses struggled to attract and retain workers. In the U.S., wage growth for leisure and hospitality workers grew by over 10% year-over-year in mid-2021, much higher than during previous recoveries.

Past Recessions: Typically, wage growth remains subdued after recessions due to slack in the labor market. Employers usually have a large pool of available workers to hire from, which keeps wages low. Wage inflation was much slower in previous recoveries like after the 2008 crisis.

5. Labor Market Churn and "The Great Resignation"

COVID Recovery: Another weird feature of the post-pandemic labor market was "The Great Resignation," where millions of workers voluntarily left their jobs in search of better pay, benefits, and work-life balance. In the U.S., over 4 million workers quit their jobs each month through much of 2021, reaching record levels of job turnover.

Past Recessions: Voluntary quits typically decrease during recessions, as workers prefer to hold on to their jobs due to economic uncertainty. The scale of resignations and labor market churn during the COVID recovery was unprecedented.

6. Government Support and Job Preservation Programs

COVID Recession: Governments around the world implemented unprecedented job preservation programs(e.g., Paycheck Protection Program in the U.S., furlough schemes in Europe). These programs helped keep millions of workers on payrolls, even as businesses temporarily closed or reduced operations. As a result, many workers avoided outright layoffs and were able to return to work quickly once restrictions eased.

Past Recessions: While governments have provided unemployment benefits and economic stimulus in previous recessions, the scale and scope of the job preservation efforts during the COVID recession were unique. Programs like PPP and furlough schemes were designed specifically to prevent the kind of mass layoffs seen in previous downturns.

Have we learned the wrong lessons?

So far, things have turned out pretty good post pandemic.

Inflation

Most people would probably argue that inflation has been the biggest issue.

I don’t love paying more for stuff any more than you do, but there’s a rational argument that when taken in a long-term historical context, inflation isn’t horrible.

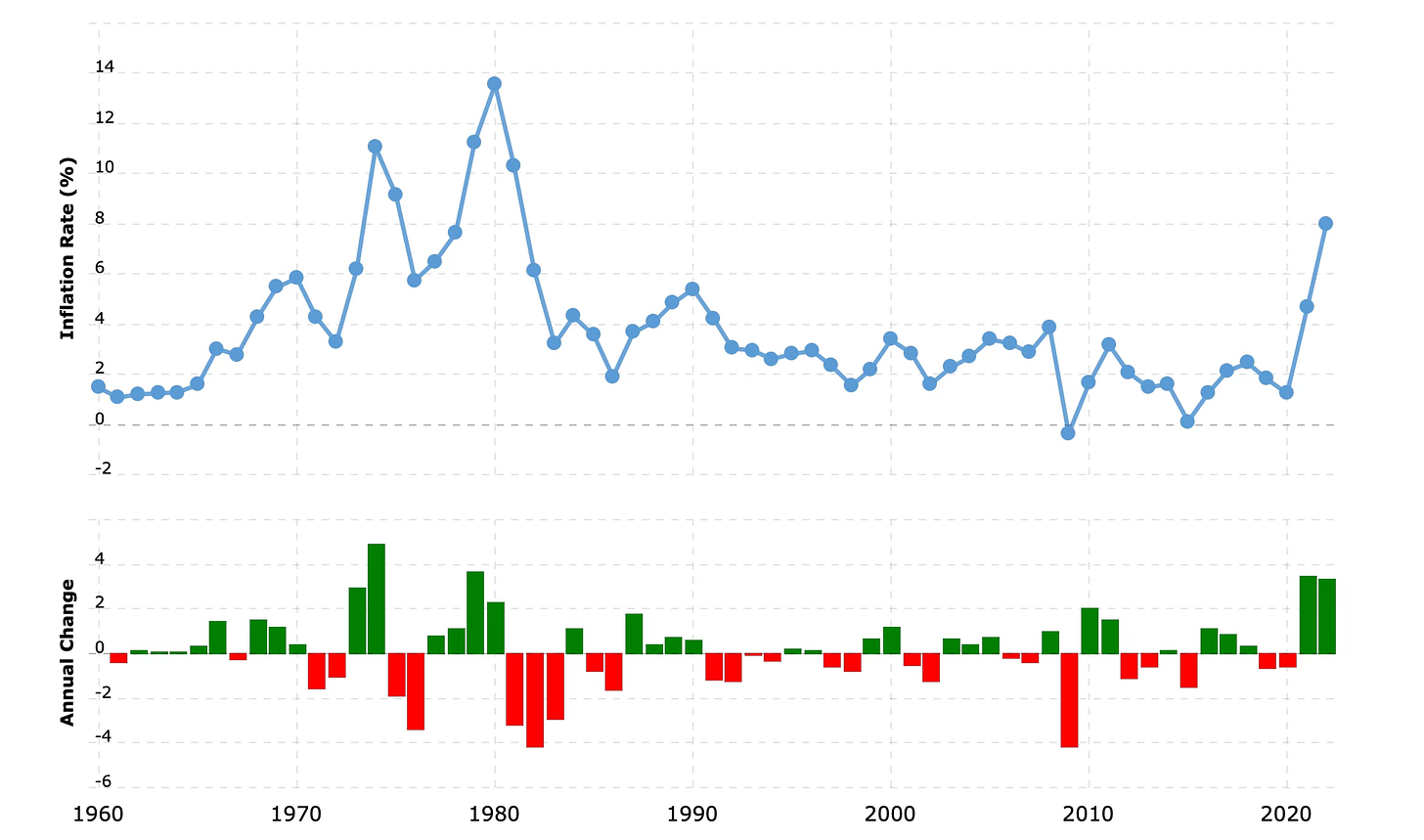

2% is the Fed’s target rate. Look at the 2% line on the Annual Change chart below.

Minus the last 2 years, we’ve been below the target since 1980.

Rate hikes

The speed and magnitude of the Federal Reserve’s rate hiking cycle in response to post-COVID inflation was historically fast and aggressive.

Yet we didn’t see widespread credit crises, bankruptcies, or other huge issues.

It didn’t spark big layoffs, or dramatically slow consumer spending.

2022 Bear Market

I’m putting this here, because I think the rates were the primary driver.

Let’s put 2022 in historical perspective:

Magnitude of Decline

In 2022, the S&P 500 fell by about 25% from its peak, which is significant but not extreme by historical standards.

Historically, bear markets have seen average drops of around 33%.

Speed of the Bear Market

The decline in 2022 unfolded over most of the year, a more gradual drop than other bear markets.

Other bear markets, like the 2008 crash, were faster and more intense. In contrast, 2022 was marked by a slow grind lower, as inflation, rising interest rates, and recession fears wore down investor sentiment over time.

Drivers of the Downturn

Unlike previous crises driven by financial system failures (2008) or asset bubbles (2000), the 2022 bear market was primarily caused by the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes to fight high inflation.

Recovery Time

Historically, bear markets tend to last about 9-18 months and take a few years to fully recover. The 2022 bear market fit into this timeline.

Recoveries from bear markets tied to inflation and interest rate hikes, like the 1970s, have typically been slower than those caused by more acute financial crises. Based on that, we can argue that the 2022 bear market was a fast recovery.

Recession indicators

The yield curve inverted and we didn’t get a recession.

The Sahm Rule was triggered, yet we just got a banger of a jobs report.

Risk means more things can happen than will happen.

— Howard Marks

None of this had to turn out this way. A recession was widely predicted, yet here we are. No recession (as of yet).

The way a lot of this turned out seems unlikely to me. But I wonder if people are projecting a lot of lessons forward that maybe we shouldn’t be?

Things like:

Massive government stimulus can stop a recession

Markets will always bounce back quickly

The labor market will always bounce back quickly

Interest rates don’t matter that much

The 2020 and 2022 bear markets didn’t bother me too much, I’m an emotionally sound investor

Conclusion

I’m not making any calls for a recession, or that things are about to get worse.

I do think that things have turned out better in the past few years than almost anyone would have predicted.

I also think that a lot of what we’ve seen in the past few years has been very different than what we’ve seen in the past.

That begs the question “is this time really different?”

I have no idea.

But I do wonder if investors believe that it is. They could be right.

But it’s also possible that we’ve seen a string of anomalies, and strange economic events that we shouldn’t be projecting into the future forever.

That’s why more and more I’m trying to not to solve those kinds of hard problems. Instead, I’m looking for direct returns from the companies I own and absolute no-brainers:

Einhorn on direct returns:

‘We believe that the strong returns and alpha from the long book came from a successful adaptation of our style. We have become even more disciplined about price and emphasize investments where we get paid by the issuers, as opposed to relying on other investors to revalue the security. Payment can come to us in the form of buybacks, dividends, interest, or in some cases, a take-out from a buyer. With the decimation of the active fund management industry, we don’t believe we can reasonably expect securities to be re-rated by investors who are actively trying to figure out what they are truly worth. Many of our largest holdings are offering double-digit returns directly to investors.’

— David Einhorn's Greenlight letter 1/22/24

Munger on no-brainers:

‘We have no system for having automatic good judgment on all investment decisions that can be made. Ours is a totally different system. We just look for no-brainer decisions. As Buffett and I say over and over again, we don’t leap seven-foot fences. Instead, we look for one-foot fences with big rewards on the other side. So, we’ve succeeded by making the world easy for ourselves, not by solving hard problems.’