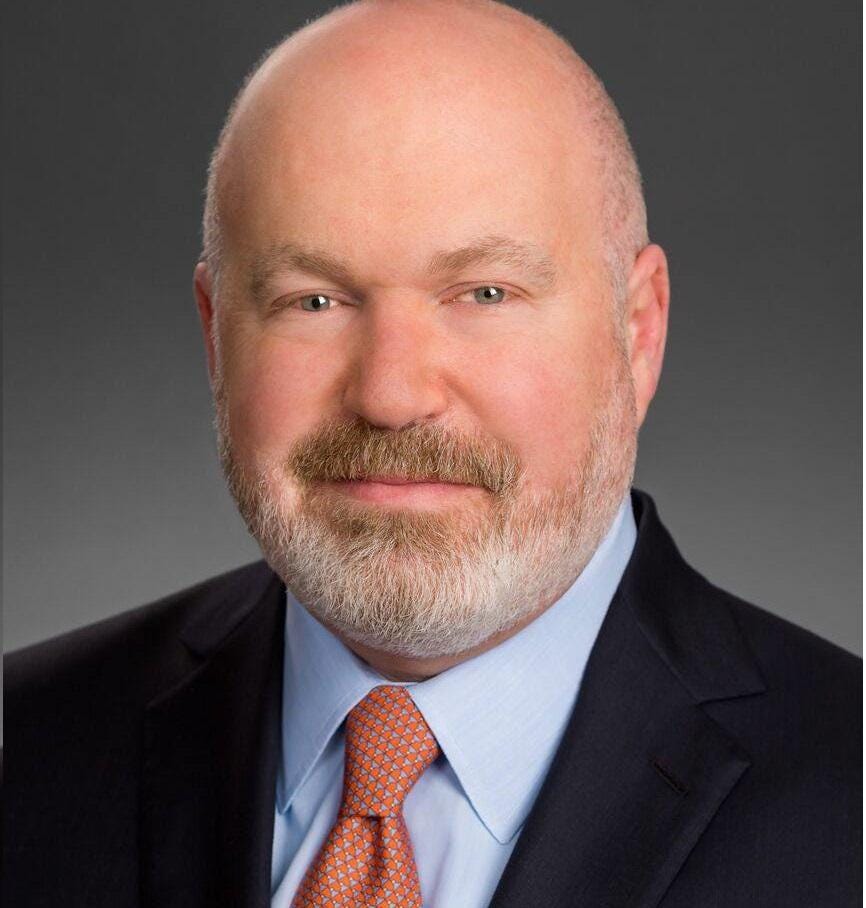

Cliff Asness is a co-founder of AQR Capital Management, a quantitative investment firm known for its data-driven approach to asset management.

He released a new paper called “The Less-Efficient Market Hypothesis” at the end of August that presents some of the best arguments I’ve seen for some of the inefficiencies that appear to be in the markets.

This article will be my summary of the paper, with some of my own thoughts thrown in.

You can read the whole thing here.

Cliff’s Key Takeaways

An efficient market is important for society

Cliff believes the market has become less efficient over his career

That leads to both a higher risk and a higher potential reward for disciplined, value-based stock pickers

An efficient market is important for society

Efficient markets matter to society.

Prices assigned to companies influence how society distributes resources. A more efficient pricing system leads to a more effective economy and helps direct resources to their best uses.

Inefficient markets lead to inefficient and less innovative economies.

The market has become less efficient

The efficient market hypothesis is difficult to test.

It makes intuitive sense that asset prices would reflect all the available information. The problem lies in the fact that there is no perfect market or model to compare it to. So to test EMH, you need a model that somehow decides what information needs to be incorporated into the price, and how it should be factored in.

If the EMH fails against this model, you don’t know which part has failed - if all the information wasn’t incorporated, or if it was done incorrectly.

Perfect efficiency probably isn’t a reasonable expectation.

So the real questions should be:

How efficient is the market currently?

Has this changed over time?

Proof of inefficiency

This is where Mr. Asness argues that inefficiency has increased over his 30-year career.

Again, there is no perfect model to compare the market against, making it difficult to determine if the market is inefficient and to what extent.

As a proxy, Asness looked at the value spread - the ratio of expensive stocks to cheap stocks.

He used a traditional price to book model

And a more complex “quant” model using 5 different ratios:

Price to book

Price to cash flow

Trailing PE

Forward PE

EV / sales

You’ll notice they both look similar, showing pretty extreme spreads in 2000 and 2019-2020.

They looked for reasons that “this time was different”

Were the spreads a function of tech stocks?

Did intangibles drive the spread?

Was it the FAANG or Mag 7?

Was value less attractive because things like ROA, profitability, etc were lower?

Was it the low interest rates?

The answer for all of them was “no”.

The takeaway:

Spreads are wider than ever, and last longer than ever.

This makes it very hard to stick to rational, value-based strategies. Longer periods of underperformance are hard to endure and justify. Investors move their money away from value managers into indexes or other strategies.

I don’t think Cliff is wrong here, and none of this is new. It’s just background to set up what I think is the best part of his paper.

His explanations for why.

3 Hypotheses

1. Indexing has ruined the market

This is the David Einhorn argument.

That there is so much passive investing, it’s ruining price discovery. If everyone indexed, then this would be true - there would be no price discovery. But we’re not there, so it’s a purely theoretical argument. Let’s find something that’s actually useful.

The real question is how much of the market can index without getting crazy prices and outcomes?

Unfortunately, we don’t know.

Passive investing is taking a bigger and bigger share of the market:

But Clifford believes that passive investing gets more blame than it deserves. I think he’s right.

He conducts a “somewhat obnoxious” thought experiment, but it gets the point across.

Imagine that some portion of investors holds the index, another group tries to outperform.

The active group is further divided like this:

Some are going to be minnows who make bad decisions based on emotion, story, behavioral biases, etc.

Some will be sharks who do well by taking the other side of the minnows’ trades.

In this world, the level of inefficiency will be dictated by which group is larger - the sharks or the minnows.

Asness argues that because indexing is the “smart” thing to do, combined with the declining popularity (and capital) of value managers, it’s likely that there are more minnows than sharks, leading to more inefficient pricing.

Asness doesn’t put it in the paper, but there’s plenty of data to back this up.

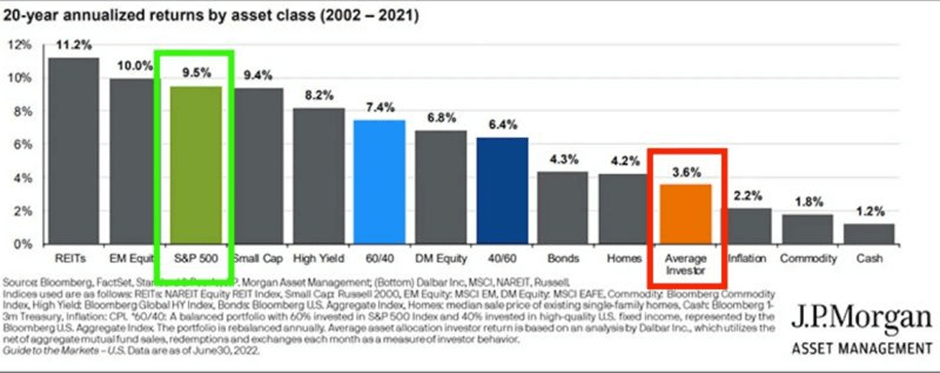

Dalbar found that the average equity investor earned 5.5% less than the S&P 500 in 2023, the 3rd largest investor gap in the last 10 years.

J.P.Morgan has similar findings:

2. Very low interest rates for a very long time

Asness says that if this applies, it only applies to the 2020 period. I’m not sure that’s true.

Considering Howard Marks’ “sea change” idea, rates have been falling for a long time:

Overall, low interest rates probably aren’t enough on their own to make the market go crazy, but they probably don’t help.

My own thinking says that they might drive up valuations overall because the cause the risk-free rate to be lower, but they probably don’t explain the value spread.

I think of them as fuel on the fire, but probably not the match that lit it.

3. We have the effect of technology backwards

Mr. Asness says this is his best hypothesis for the rise in inefficiency we’ve seen.

I agree with him. Here’s how he lays it out:

Crowd Wisdom

Any decently efficient market relies on the wisdom of crowds. However, to have a wise crowd, the members need to be independent of each other. If one person or idea gets too much influence in the crowd, it’s no longer wise. In fact, it could become a net negative. With that in mind, I’ll directly quote Asness:

So, has there ever been a better vehicle for turning a wise, independent crowd into a coordinated clueless even dangerous mob than social media?

Gamified Trading

Asness makes another great point when he talks about the gamification of investing.

Another direct quote:

imagine video poker where the odds were in your favor. That is, all the little bells and buttons and buzzers were still there providing the instant feedback and fun, but instead of losing you got richer. If Vegas was like this, you would have to pry people out of their seats with the jaws of life. People would bring bedpans so they did not have to give up their seats. This form of video poker would laugh at crack cocaine as the ultimate addiction. In my view, this is precisely what on-line trading has become over the last several years.

Now, imagine that casino on your smartphone, where you have access to it 24/7. That’s exactly what Buffett was talking about with this quote:

“For whatever reasons, markets now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young. The casino now resides in many homes and daily tempts the occupants.” - Buffett

Lots of people think that faster access to more data and lower trading costs would lead to more efficient markets. Cliff points out that these things have improved speed, not necessarily accuracy.

As Asness says in his paper - getting the information was never the problem, the problem has always been correctly interpreting it.

So what’s it all lead to?

Higher risk and a higher potential reward for disciplined, value-based stock pickers

Cliff concludes that bubbles may occur more often, in larger magnitude, and last longer than in the past.

This means that disciplined, value-based strategies may make more money in the long-term. The downside is that they’re going to be harder to stick with. The periods of underperformance will be more severe and will last longer.

What are investors doing about it?

Indexing more

Hiding in private equity

Moving to momentum / trend following

The most interesting of these three for me was private equity. Asness points out that the low liquidity, lack of daily pricings, and the fact that PE isn’t marked to market fix a lot of the behavioral mistakes the public markets force investors to make. The downside is that the trade is getting crowded, and the returns will likely be lower than in the public markets.

What should investors be doing?

Cliff offers 5 pieces of advice:

Try to become as logical and rational as possible, while recognizing that you’re human and can’t be perfect.

Study history

Recognize that drawdowns and underperformance feel longer than they are.

Have as long of a time horizon as possible

“a long-term horizon is the closest thing to an investing superpower”

Look at the portfolio, not individual pieces

If you’re actually diversified, something will always be underperforming. Remember why it’s there.

Accept that higher rewards come with higher volatility. Size your positions appropriately

Improve your process

Conclusion

Here are Cliff’s conclusions:

Markets are less efficient

Technology, gamification, 24/7 trading on phones, social media are likely the biggest culprits

Ups and downs will be bigger and last longer

That will make more money for people who can stick to it long-term, but it will be harder to do so

Indexing is a very reasonable option for those who can’t stick with it

Old-school, active value and quality stock-picking have had lots of people leave the strategies

Creates an opportunity for smart investors to take advantage of

Here’s mine:

I think Cliff makes a pretty convincing argument. If you’ve spent any time at all on social media, especially Reddit or the platform formerly known as Twitter, you’ll see the crowd becoming mob-like.

Cliff didn’t mention it, but I think his paper makes a really strong argument for saying no to most ideas and only investing in no-brainers.

You can read more of my thoughts on that here: